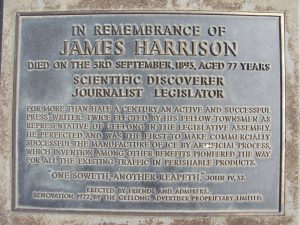

Meet James Harrison – a Scotsman who arrived in Sydney in 1837, worked as printer on the Sydney Morning Herald, and then invented the world’s first commercially viable ice-making machine to chill beer and freeze meat. He should be more famous, but he isn’t. We should have studied his life at school, but we didn’t.

Queen Victoria ate thawed Australian lamb thanks in part to one of the great unsung heroes of Australia, James Harrison.

Harrison founded the Geelong Advertiser newspaper and was a member of the Victorian Legislative Council and Victorian Legislative Assembly. Others were involved in the early years of refrigeration, but Harrison is attributed as the inventor of a practical mechanical refrigeration process of creating ice. He was also the founder of the Victorian Ice Works and as a result, is often called “the father of refrigeration”.

Harrison’s role as a printer, it turned out, was crucial. Metal type needed regular cleaning with sulphuric ether. Scrubbing away, Harrison noticed that ice crystals formed when he blew on the raised letters.

A few kilometres from town, he located a large cave, close to the Barwon River. After some occasionally explosive experiments, he perfected his machine: one that could make commercial quantities of ice.

Granted a British patent in 1855, he was soon selling his machine around the world.

Soon after, he was commissioned by a brewery to build a machine that could cool beer. His system was almost immediately taken up by the brewing industry and was also widely used by meatpacking factories.

He won a gold medal at the Melbourne Exhibition in 1873 by proving that meat kept frozen for months remained perfectly edible.

That year he decided to invest all his funds in an historic first: an attempt to take frozen Australian meat to Britain. Unfortunately, on the 34th day halfway to London, the consumption of ice was greater than expected. As temperatures rose all 20 tons of meat had to be thrown overboard. His choice of a cold room system instead of installing a refrigeration system upon the ship itself proved disastrous.

Harrison arrived in Britain, meatless and mirthless, a broken man.

This disaster not only bankrupted Harrison, but also ruined public confidence in refrigerated meat at that time.

Not long after in 1879, a different team competing for £100,000 pulled it off using a slightly different method of refrigeration using a specially constructed cool chamber: Queen Victoria, no less, sat down to eat a thawed piece of Australian lamb.

Harrison missed out on any mention, even though he was responsible for probably the most important single innovation in terms of its impact on living conditions in a hot climate.

The Smithsonian Institute in Washington exhibits a model of Harrison’s refrigeration plant.